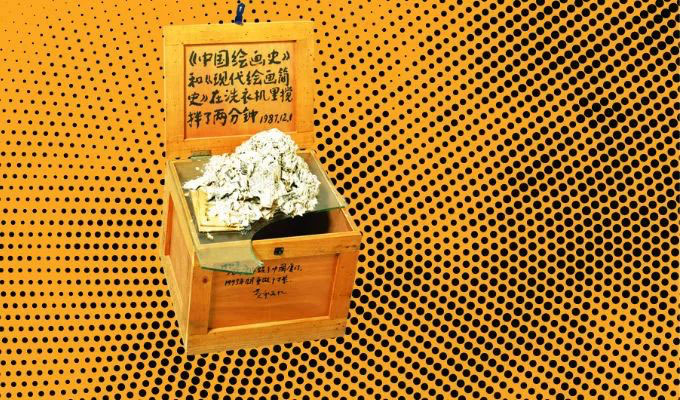

In 1987, Huang Yongping plonked one copy of “The History of Chinese Painting” and one of “The History of Modern Western Art” into the washing machine for 2 minutes. The result: a pile of papery mush on top of a wooden box, and one of the most iconic works of Chinese contemporary art.

Hang on… what?

It might sound like a load of indulgent, arty farty pulp, but Huang’s work is deserving of place, for it succinctly summed up a major turning point in Chinese art history. Following Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening” of the late 1970s, an influx of books on art and philosophy flooded in from the West, giving meaty fuel for creativity, as well as highly charged discussions on the purpose and direction of art in China.

Several centuries of Western art history were gobbled up, digested and spat out in a matter of years, as Chinese artists grappled with new ideas such as conceptual art, or art that need not “serve the people”, nor even produce material objects. This frenzy of theory and practice, however, left artists and critics somewhat confused. Like Huang’s pile of pulp, they could not work out where Chinese art now fitted between tradition and modernity, East and West.

On the one hand, abandoning tradition was trendy, as artists reached for novel materials, such as oil paint and plastic, and alternative modes of expression; installation and performance, for example. Famously, a Dada group developed in Xiamen, which was all about subversion. They believed that only by burning an artwork could its value stay the same forever.

Skill was traded for concept, as artists tackled completely new subject matter. Wang Jin’s 1996 installation “Ice”, a 30m wall of commodities frozen in blocks of ice, exposed a society hungry for consumerism, as they hacked away feverously to defrost their desires. Zhang Dali spray painted his profile on over 2,000 walls throughout Beijing in a “dialogue” with the city, before swathes of it were torn down to be rebuilt.

Traditional arts, on the other hand, did not simply evaporate, but were challenged to find new relevancy in a rapidly changing environment. In 1985, Li Xiaoshan, a postgraduate student at Nanjing University of the Arts, declared that Chinese painting had already achieved all it could. It was at its dead end.

Li argued that in almost 2,000 years of feudal society, Chinese painting remained astonishingly stable, which had prevented the development of art as ideology.

“Contemporary Chinese painting is at a turning point, between crisis and rebirth, destruction and creation. The worry, anxiety, reflection and contemplation experienced by contemporary Chinese painters reflects historical evolution.”

The art world was stunned. His frank opinion caused a sensational because it resonated with so many painters at the time, many of whom were too afraid to confront reality. Yet, confrontation and change drives art. By washing the histories of Chinese and Western art, Huang Yongping was not only cleansing and destroying the past, but paradoxically, he was also engaging with it. Only by doing so, could Chinese art continue to develop and thrive and come to be what is now one of the strongest players on the art market today.